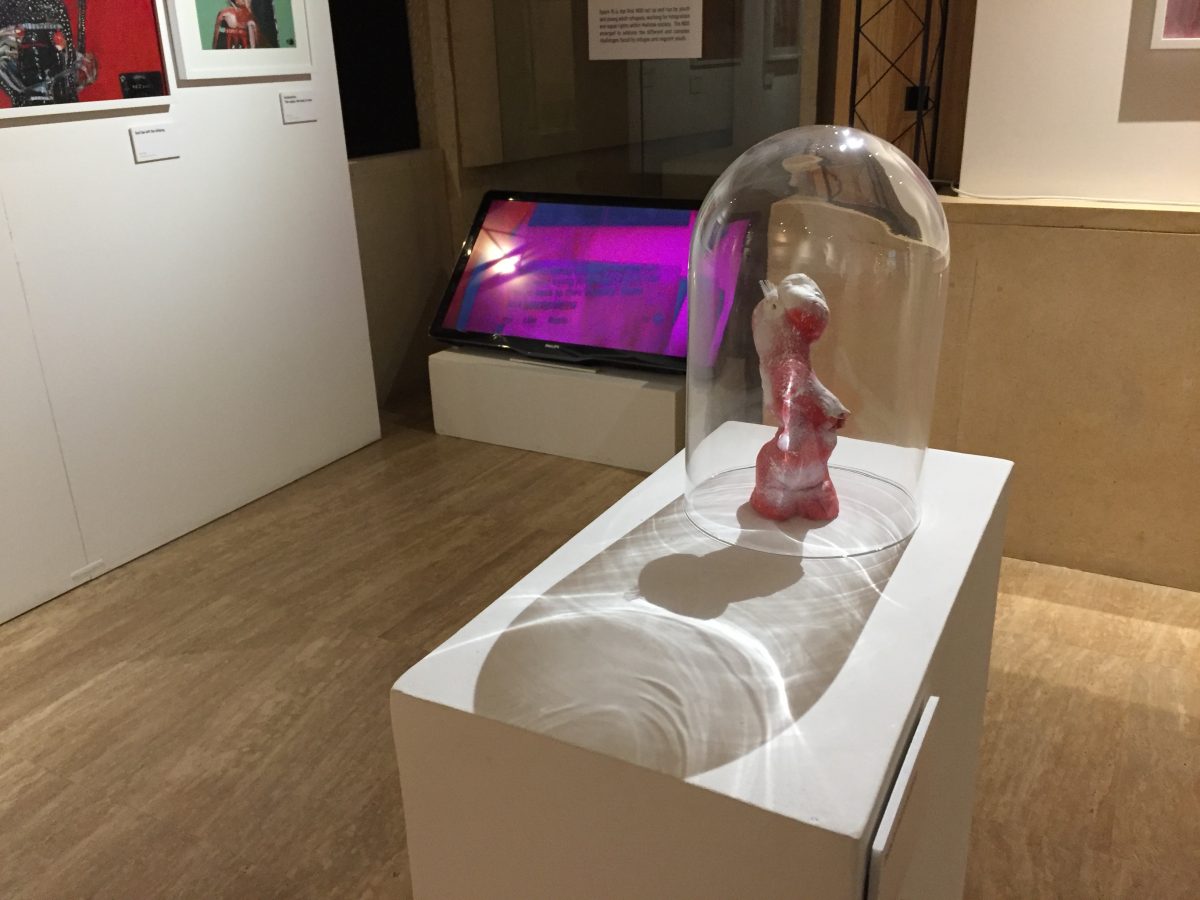

Dehumaneation, 2021

Featuring work by artist Shaun Grech, Dehumaneation (15 January-28 February, 2021, Spazju Kreattiv, Valletta) combines three concepts: dehumanization, humiliation and nation. Curated by Raphael Vella and with creative input from Paul Portelli, Martin Bonnici and the NGO Spark 15, Dehumaneation deliberately mixes paintings, souvenirs, reproductions of Old Master paintings, a variety of objects, sculpture, film, installation and found text and images, especially hate speech found on social media.

The Necessity of Belligerence

Raphael Vella

Categorisation disposes of the world’s disorder. Scientific disciplines revel in it; some might say that life as we know it depends on it. Without the identification of symptom clusters, what hope would there be for medical diagnoses? Without hierarchical species structures, what sense would biology make? How would algorithms function if new data couldn’t be classified into established categories? Some might argue that in a world without categories, communication itself becomes impossible. For how would I bear witness in court if I couldn’t decide whether the person I observed entering another person’s residence was young or old, tall or not-so-tall? How could we tell good from bad weather during our banal conversations with strangers? And so on. The very fact that I’ve just used the phrase ‘and so on’ implies that I’ve dumped all the previous questions into a single mental category. In other words, that phrase seems to indicate that the different questions are actually substantiating the same rhetorical idea, more or less.

We need mental dumping grounds of this sort. There you have it…I’ve just used the word ‘we’– that representative of plurals, families, assemblies, collectives, political and cultural distinctions. ‘We’ defines the strength of a fan base: it’s what draws you to one side of the football stadium where you see thousands of others wearing the same coloured scarves and waving the same flag as you. The spectators occupying the opposite stands wear and wave a different colour: it’s us and them, home and away, blues versus reds. Nothing is simpler or more distinctive than coloured jerseys, nothing more innocently tribal than sports.

Except, of course, when ‘foreignness’ comes knocking at your door. If you let it in, how will the ‘we’ within be transformed? Boundaries like doors, walls and stadium divisions are effective so long as whatever is outside remains there. Take outsider art. If outsider art is shown in a regular art gallery, does it become ‘insider’ art? Mainstream art? Indeed, what lies outside outsider art?

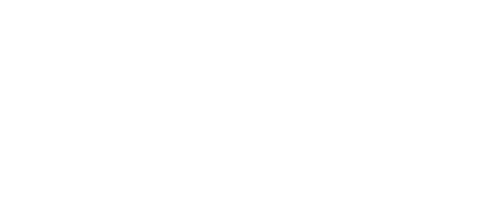

It might be something like Shaun Grech’s paintings, which exhibit the sort of obsessive qualities that could belong to the genre of outsider art but don’t fit snugly into that category either. Grech’s paintings are bold yet untrained (or untrainable), like Ted Hughes’ raging jaguar who “spins from the bars, but there’s no cage to him”. They might be interpreted as ‘naïve’ – that other classic attribute of outsider art – because the frightening faces that populate them share so many features amongst themselves they would probably have belonged to the same family had they existed. One could argue that Grech’s characters collectively form their own physiognomic ‘norm’ even though they simultaneously deviate completely from real, human norms. Yet, Grech’s obvious academic background belies the ‘naïve’ attribution, leaving his painted characters dangling in an indefinable in-between space.

It’s precisely this sense of uncertainty that lures viewers towards these faces only to deny them a clear analysis or identification with any of them. The lingering questions “who are these people?” and “am I supposed to like or loathe them?” seem to be corroborated by Grech’s intuitive approach to the medium of painting. Stylistically and chromatically, the images feel spontaneous, unlaboured, a little like the squiggles of a child who couldn’t care less about adult preconceptions surrounding ‘research’.

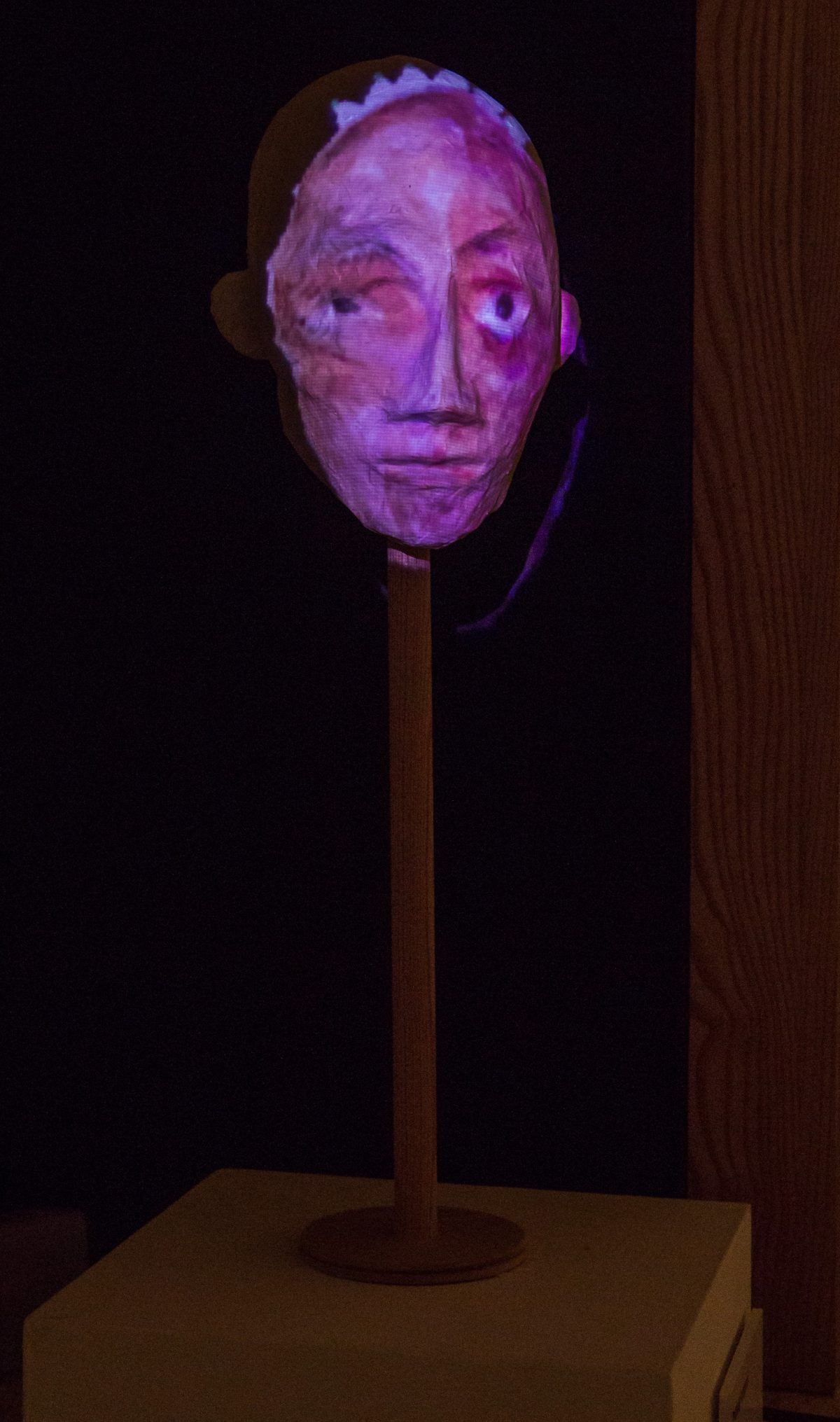

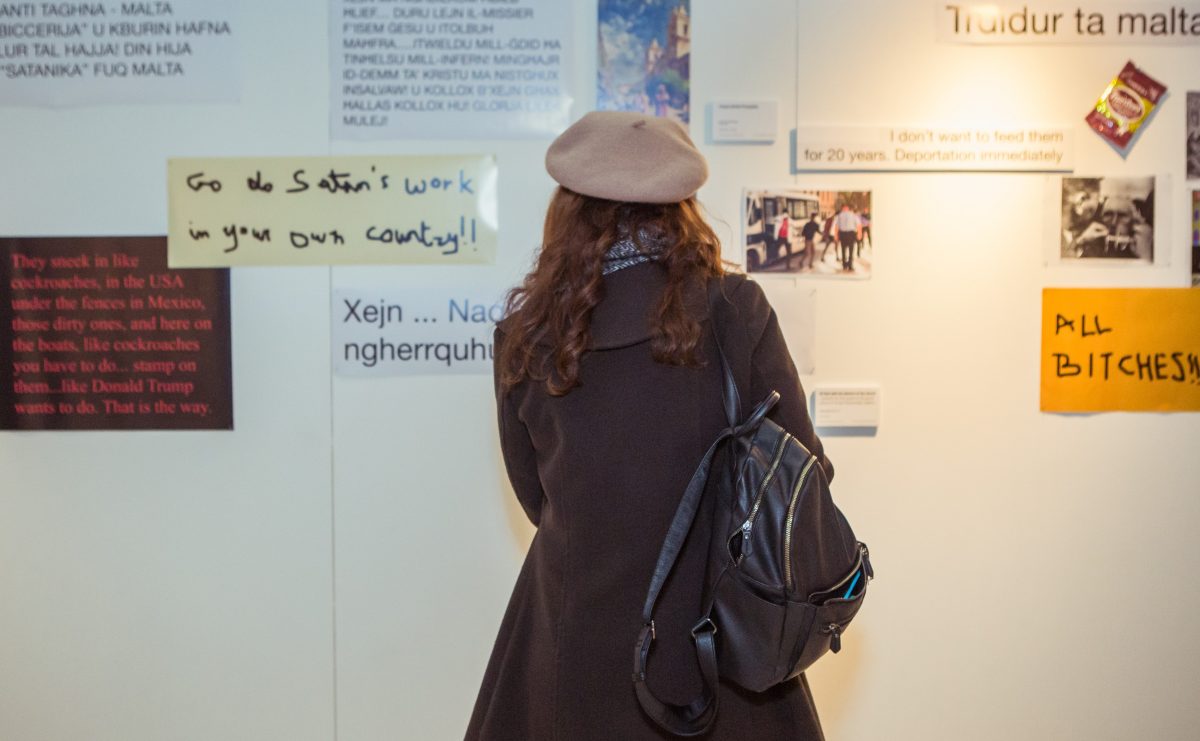

But what really matters in Grech’s paintings and other objects (collected photographs, Facebook texts, religious paraphernalia) is their anger, because anything milder than anger or aggression would only work to preserve the status quo. Logical thinking won’t dismantle constructed hegemonic categorisations of man and woman, white and black, local and alien, normal and abnormal, positive and negative, citizen and non-citizen, inside and outside, all of which only serve to construct difference and marginalise. It won’t challenge the classifying ruptures that facilitate an architectural organisation of knowledge or the algorithmic separation of classes of data. It won’t protect migrants from the humiliation of being told to go back to their countries because they do not belong ‘here’. Logical thinking will probably not be sufficient for some people to be convinced of the inconclusiveness of essences: those objectifying indicators of belongingness assumed by religious faith, food, clothing, or a flag. Indicators that connect bird-trapping to tradition, pork sandwiches to Catholicism, skin colour to nationality and citizenship. And it won’t safeguard critics of these monolithic and ill-informed indicators against being called ‘traitors’.

It won’t help you to think the ‘unthinkable’.

Dehumaneation – Grech’s paintings and all that populates his work – expresses anger not because the artist fights fire with fire. True, his work may not be politically (or even aesthetically?) correct, but it never echoes the hate speech he abhors so much either. Grech’s struggle takes place on a different plane, in an undefined place where relations are not bound by the imposture of blues versus reds, outsider and insider, art and non-art. It’s a passionate expression of indignation that is provoked by indisputable [un]certainties and unjust exclusions – the kind of exclusions that oppress, that rule out the possibility of hospitality from the start. Beyond their common features and stylistic qualities, Grech’s images share this ethical belief in the importance of caring about those who wait at the borders, whose lives are interrupted by ‘common sense’ categories like us and them, inside and outside. Paradoxically, hospitality sometimes depends on the odd marriage of belligerence and love.

Photo credits: Top five photos by Elisa von Brockdorff. Remaining photos: Raphael Vella

Date

- January 23, 2021