Tunis-Malta-Marseille, 2021

Featuring the work of French artist Katel Delia, the exhibition Tunis-Malta-Marseille combines archival photos with photographs by the artist and various objects and items of furniture.

Domestic-nomadic spaces

Migration always implies a personal upheaval, because for most migrants it involves a leap in the dark. Yet, migration usually also incorporates broader dimensions that transcend the individual, as considerations like migration policies, labour, family, community and citizenship come into play. While no two migrants’ stories are the same, many realities experienced by migrants, especially those following similar migration routes, are shared. These overlaps in migrants’ narratives help us piece together societal tendencies, attitudes and behaviours, leading to better understandings of the likelihood of hospitality or the much more calamitous reality of rejection.

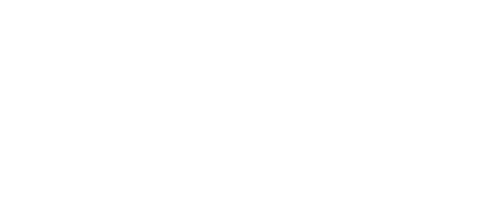

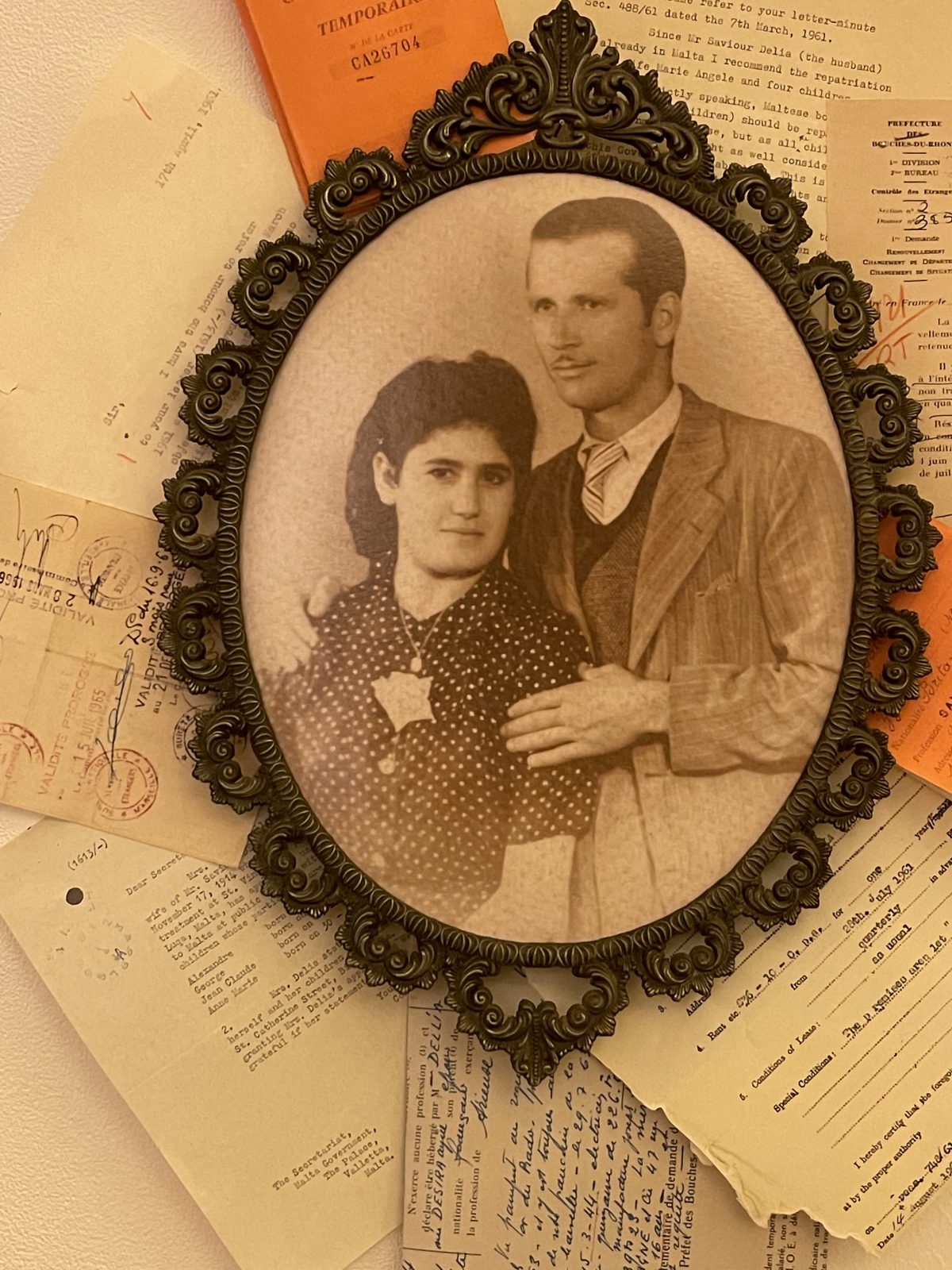

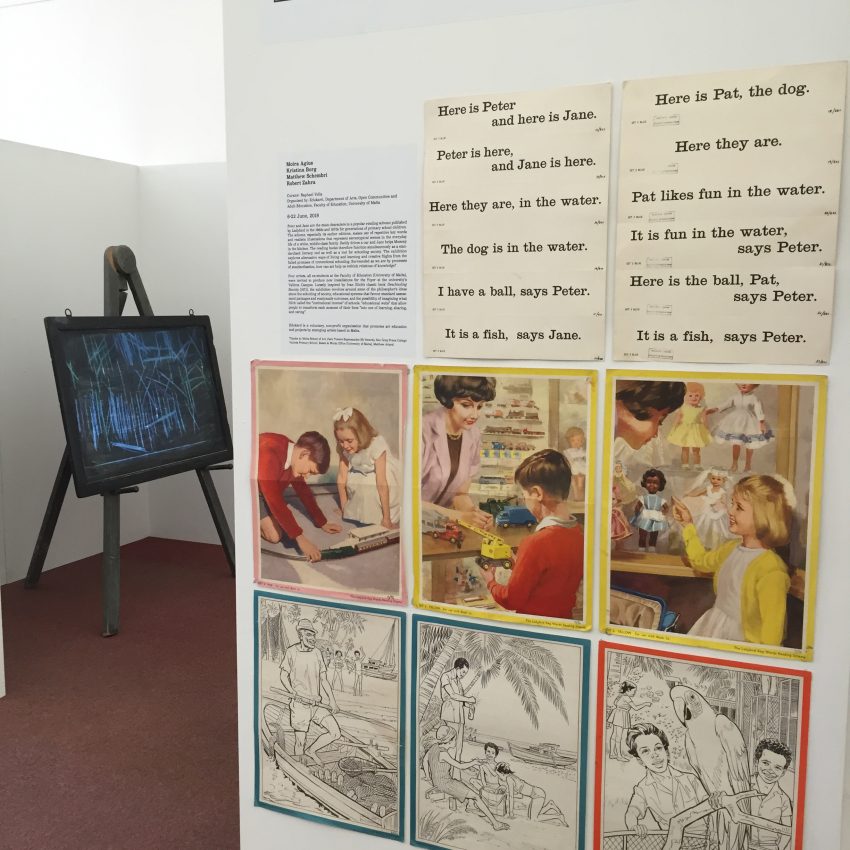

Malta – Tunis – Marseille, Katel Delia’s exhibition on migration in the Mediterranean, revolves around a similar balance of the individual and the collective. It tells a rather personal story, tracing the artist’s family history of movements between Malta, Tunisia and France over four generations. This is not the kind of history that is moulded out of clear, chronological narratives; rather, it focuses on the notion of history as a series of representations as the artist deliberately feeds anachronisms into her imagery. Some factual details about location are identifiable while others are only assumed. History is told through a studied selection of old and new photographs taken in Tunis, Marseille and different parts of Malta, often mixing archival images with more recent ones that the artist shot during her travels. These careful juxtapositions project the past back into the present, highlighting the idea that the past’s meaning can only be grasped fully with the intervention of one’s imagination.

History’s presence is also transmitted in a collection of objects scattered around the exhibition spaces – random things like a little bird cage, a weighing scale, an old telephone and items of furniture that evoke personal meanings associated with home, family, hobbies, aspirations, work, and so on. Again, while some objects are factually linked to the artist’s family (particularly her father), others that the artist bought second-hand act out a role in a theatrical scene that does not seek the truth only in archival evidence but also in an imagined history.

It is precisely this strong imaginative flavour throughout the exhibition that safeguards the artist’s project against the dangers of solipsism. Letters, photographs, medical and other records of the Delia family become much more than a family scrapbook or photo album. Essentially, they become metaphors of broader concerns: social structures, urban mobility, linguistic utterances, cultural intersections and desires.

Curatorially, the exhibition maps out a nomadic travelogue by moving from the macro, geographical field to the micro space of the home. Three countries (Tunisia, Malta, France) are translated respectively into shop, living room and bedroom. The different furniture and colour tonalities in these three spaces help to shape a history of commercial activity, leisure and family life. They also evoke a sense of movement as well as retention, as the artist asserts that the migrant will always bring along something from his or her last home. This is why the rooms have constructed ‘walls’, just like territories have constructed borders, but we also get glimpses of what lies beyond these walls, doorways and passages. The dissection of space into different entities does not rule out the possibility of connections. Objects found in one ‘country’ reappear in photographs on the walls of another place. Personal and collective memories help us to make sense of our lives. And nothing speaks of home and safety as much as a cosy bed.

Mass Maltese migration to Tunisia predates the establishment of the French protectorate in 1881, yet the stories of migrants settling there after leaving the island are not as well-known as those in other Maltese diasporic contexts. The different stages of Katel Delia’s family relocation shift from Malta to Tunisia, then back to Malta and finally moving on to France. The last stages involved her relatives in internal French migration, as the family moved from Marseille to Brittany, while the artist then chose to live in Paris and finally Malta later in life.

Migrating from one’s home country to another (and then again to another) is never an easy decision, though many migrants say that they never really had a choice. However, unlike the stories of ruthlessness and exploitation many associate with African migration in the southern Mediterranean in recent years, Malta – Tunis – Marseille is not a story of despair. Nevertheless, one finds indelible traces of longings for peace and sanctuary in it that should help many local visitors connect the experiences of African refugees today with their own family history and possibly their own lives. The domesticity of Katel Delia’s exhibition spaces acts as a metaphor for a regular, stable livelihood and a basic humanity, for this is ultimately what all migrants long for.

- September 21, 2021